Synopsis

In this stunning graphic novel, Lacuna is a girl without a family, a past, or a proper home. She lives alone in a swamp made of ink, but with the help of Polaris, a will-o’-the-wisp, she embarks for the fabled Northern Kingdom, where she might find people like her. The only way to get there, though, is to travel the strange and dangerous Blue Road that stretches to the horizon like a mark upon a page. Along the way, Lacuna must overcome trials such as the twisted briars of the Thicket of Tickets and the intractable guard at the Rainbow Border. At the end of her treacherous journey, she reaches a city where memory and vision can be turned against you, in a world of dazzling beauty, divisive magic, and unlikely deliverance. Finally, Lacuna learns that leaving, arriving, returning — they’re all just different words for the same thing: starting all over again.

Review

Thank you to Edelweiss+ for the free digital ARC!

Read: September 2019

Rating: 4.5 stars out of 5

This book definitely feels like it’s written for a younger demographic. Think elementary and middle school kids. But that doesn’t preclude adults from appreciating it – particularly if they’re like me and follow politics.

Art style can really screw up a graphic novel. Hiromu Arakawa’s Fullmetal Alchemist is one of my all-time favorite series – not just for the plot, but also for the gorgeous yet realistic (for manga, anyway) line art. On the other hand, while I comprehended the purpose of Octavia Butler’s Kindred, my enjoyment of the graphic novel (adapted by Damian Duffy and John Jennings) was seriously hampered by the art style. De la Noche Milne’s art does not follow the refined, crystalline style you might see in a museum or the starkly inked fashions typical of manga. Her illustrations have a smudgy, myopic quality that meshes with the fable genre of the book. Fables tend to be vague things: their details are minimal. Their audiences are given just enough information to follow the story, with elaborations forgone in the interest of creating concise stories that can be traded easily and often without muddling the central idea. In choosing a style that does not rely on details, de la Noche Milne bolsters the “fable” theme of the tale without making the background seem barren.

Immigration has been a major subject of debate for as long as I can remember. In particular, the firestorm has grown hotter since 2015, when a witless, bigoted motherfucking Oompa Loompa Donald Trump entered the presidential race. Trump and his immigration adviser Stephen Miller have been wreaking havoc upon immigrant families, whether they’ve been long established here in America or come to our border seeking protection and better lives. So many people write off crossing the border legally as “easy”. “Just come to the border like you’re supposed to,” these folks will argue. But even the slightest bit of research unveils a hellscape for people seeking entry into the U.S. – and a continuing looming threat over the heads of those who do gain legal entry.

Compton has clearly kept all of this in mind as he crafted his various allegories for the struggles facing immigrants. Despite their symbolic nature, Lacuna’s trials aren’t difficult to connect to real-world obstacles. The thicket of tickets through which Lacuna must travel represents the bureaucratic nightmare of obtaining the proper documentation to enter the country. The mirrors allude to the constant worry that surrounds temporary statuses and the plight of Dreamers: the so-called “mirror people” must constantly look over their shoulders in order to partake in the world. Perhaps the most poignant allegory is that of the faceless people, who sometimes would escape the regime of the northern kingdom and then bear children who were not faceless themselves but to whom their parents were faceless. This could apply to a number of scenarios, chief among them the tragic tales of forced family separations by the Trump administration and the suffering of the unaccompanied minor.

Don’t think, however, that simply because these ordeals are encapsulated in allegory means that the story is devoid of some harsh elements: In one scene, the border guard quite literally slices a bird in half because it flew across the border. The slaughtering of the bird is depicted on-page, and its corpse is shown lying broken on the blue road. In refusing to shy away from this draconian act, Compton and de la Noche strengthen the narrative of the brutal tribulations endured by the immigrant.

It’s also worth noting that the main character is a woman of color. Opting to portray the main character as a white person might have been the obvious choice to some because -let’s be honest – this story is aimed at folks with anti-immigrant stances, particularly white people, and children who might lack exposure to other cultures and races. Perhaps it would be easier for these particular audiences to identify with a white person, but that kind of pandering would do the real-world component of the story no justice. One aim of The Blue Road is to evoke the audience’s sympathy for Lacuna, even if she does not look like they do. Her skin is brown, she is a young woman, and she’s an immigrant, but Compton and de la Noche impress upon the audience that none of that renders her any less human or less capable than someone who is white, male, and a “natural-born” citizen.

Overall, The Blue Road is a powerful story about a strong young woman who fights against the odds to make a life for herself and ultimately succeeds. The Blue Road is more than just some graphic novel though: It’s life for numerous people. Immigrants might not literally have to drink ink or keep their eyes glued to mirrors at every waking hour, but they are forced to grapple with even worse realities. We can do something about that, though, Compton argues. This book is perhaps his way of encouraging us to take that first step to speak up for immigrants: to both look beyond our border to understand others, and to look within the border to correct the wrongs that persist here.

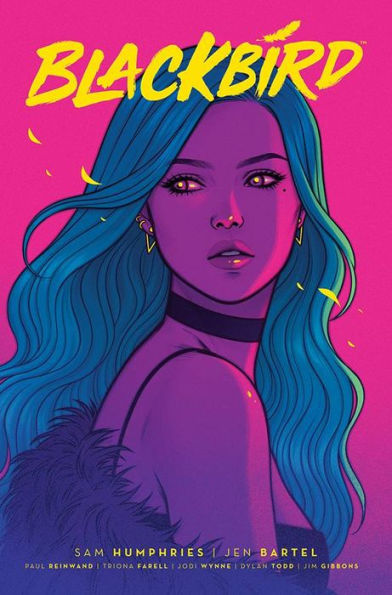

Synopsis and cover image are from BarnesandNoble.com.